So for #KidLitWomen month, I thought I’d talk about something near and dear to the part of my heart filled with the ever-burning rage-fire stoked by oh so many things, namely: how fantasy and romance (and also fantasy that includes romance) written by women for the young adult audience is often looked down the nose at by many snooty humans, some consciously doing it and some not and also why the snoot-noses are big wrongheads and why it matters.

If you can’t tell by how overwritten that paragraph is, I really miss blogging regularly. On with the show.

Recently, I was sitting at a conference talking with some writers about this particular huge hill I will die on of mine. How I was one of those teens that internalized romance as “not serious” or “embarrassing” for way too long, only to decide to actually read some so I’d know what I was talking about as an adult and then falling in love with the genre as a reader. (I had the same experience with urban fantasy, during the great smacktalking-about-it era in SFF.) Anyway, one of the authors in this conversation writes wonderful books for teens, hugely popular, which also happen to be romances and she told us how once at an event a man who was there to take care of her as an author said in passing, “Oh, I’d never allow your books in my house. I have a teenage daughter.” Who the books are for, by the way. This is never an isolated anecdote. Ask any woman you know who writes fantasy if she’s ever been treated dismissively on a panel or if a man has ever gotten up from the audience to tell her about the books by men he wishes there were more of and why aren’t people writing those now, or if they’ve followed her out into the hallway to tell her about the ways in which they thought her books sucked. (Ladies, feel free to come share in the comments. I know you’ve got some doozies.) Every romance or fantasy writer I know who is a woman has a story or twenty or a hundred like this, where it’s implied you write garbage right to your face — especially if it happens to also be popular.

Think about the offhand dismissal that’s STILL used to characterize the YA field in most mainstream articles about YA even though it was outdated ten years ago and is still outdated now. This is a bingo game you can always win. I go into every article looking for it; usually it’s in the first or second paragraph. Sometimes, if they’re being subtle, it’s phrased slightly differently two-thirds through. Sometimes it’s the subject of the entire article. Although, spoiler alert: A lot of the articles in question are highlighting male authors of YA. Good for the guys, and yet I hope they cringe when they see the inevitable phrase about standing out in “a sea of Twilight and The Hunger Games.” As if Twilight and The Hunger Games share anything in common except female authors and main characters (well, and vast success and audience overlap, more on that to come). Or the related but slightly different dismissal of the totally ridiculous plethora of teen girls saving the day in those utterly ridiculous fantasies or dystopians (meanwhile we cheer watching teens get closer on gun control than anyone else has so far; teen girls have always changed the world, oh self-self-deceived chumps who sell them short). Also, extra bingo spot if the books by women in this glancing mention are referenced only by title and any men’s books that do get included as a part of the “sea of YA” are also mentioned with their authors’ names.

The more successful a book by a man is, the more he’s treated as worthy of serious attention or at least serious treatment. The more successful a book by a woman is, the more likely it is to become the reference for a snarky aside in an article about how great X book by X dude is. Fact. But that’s not all that goes along with this behavior, not by a long shot. It affects invitations and review coverage in general and also time. If a man reaches a certain level, he’s pretty much guaranteed he can get some coverage and publisher support. If a woman reaches a certain level, she might get some coverage and publisher support but she will also be expected to do a ton of outreach to her fanbase and provide a jillion pieces of free content, et cetera.

There are so many issues surrounding all this, but for now I’m going to focus on one: how markers of traditional femininity are used to judge innate quality and why it is nonsense. The judgments discussed above have pretty well zero correlation to the works in question. The work — women’s work, specifically — is often not judged on the work itself at all, but on perceptions of it. See also: YA as an entire category, where those who supposedly “transcend” the genre are mostly men. Newsflash: The genre is transcendent all on its own; it contains multitudes.

Now, this is not news to anyone, and certainly not to women. No matter what kind of work women do, we get judged by perceptions — based on our appearance or how loud or quiet we are or or or or. And I know that there are plenty of women who write quote-unquote serious books who are frustrated that their work isn’t treated with the same seriousness of men’s serious books. I hear you.

We all judge by the cover, by appearance, by our own preconceptions, to an extent. That’s just part of how humans work. But if we want to be responsible members of the literary community (and, you know, combat these problems not add to them) we must know what our preconceptions are, where they come from, and, yes, when they are — pardon my not-French — bullshit.

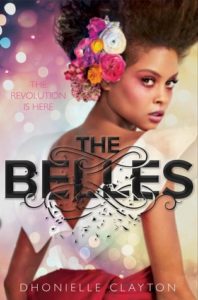

An entire essay could and should be written about how race plays into all this, as well. Whatever white women like me experience, I have zero doubt it’s 10 times (or a hundred times) worse for women of color or other marginalized writers. Witness the recent round-up of several new books by women of color in the New York Times — the grouping itself is unfortunate unless it was going to treated in a much more prominent, important way, as in a lengthy cover review (which would be absolutely apropos, these are important books and it is an important time). But, as other people, particularly Ebony Elizabeth Thomas (@ebonyteach) and Malinda Lo (@malindalo) on twitter (follow them if you aren’t), pointed out, shoving them together in a round-up is a choice that innately marginalizes the books, which include some of the most significant titles of the season. The choice of a white reviewer is also unfortunate, and there are other issues with how the books are discussed as a result. Why I bring this up here, however, is the way in which Dhonielle Clayton’s stunning fantasy The Belles is discussed, because I think it has to do with this exact subject, albeit coupled with an extra layer of racism. In this book, Dhonielle Clayton has chosen to write about oppression and slavery, but it’s done in a way that immediately gets misperceived as somehow slighter. You can’t tell me this gorgeous cover isn’t also interpreted through the preconceptions of many people to read feminine, and thus, obviously, not deep, not expertly crafted, not important.

Except this book is all of those things.

What do we code as traditionally feminine? Love, romance, beauty, fashion, care-taking, the color pink. The list goes on. And on. This cover is great because it tells you there’s traditional femininity involved here but not just that, this is a larger femininity we’re seeing, a healthier, more complicated one. The tagline: “The Revolution Is Here” and that gaze directly at the reader is as important as the flowers and the dress in setting expectations.

But we see a review in one of our most important media outlets where instead this book is pitted against another brilliant book simply because both authors are women of color writing fantasy, and a conclusion is drawn that feels related to these larger issues. We treat fantasy seen as somehow “girly” (ugh, that should mean literally ANYTHING) as the less accomplished. This is a perfect example of something far too many of us bring with our preconceptions, even professional critics, when we open a book. Awareness of this is key. But there’s an even more sinister assumption at work here. When we continually imply that only tragedy and pain are roots for telling an important, honest story — particularly when we’re placing that limitation on writers of color — what we’re doing is deciding to create a world in which we force people to relive pain on our terms, not theirs, to tell the stories we expect, not the stories they need or want to tell. I mention this here because racism is a part of every single discussion we’re having this month (and always), in one way or another. We’ll only be successful at toppling the hierarchies we want to break down if those hierarchies topple for all writers, especially traditionally marginalized ones.

Likewise, in fantasy, women who present with traditionally masculine traits are often considered “strong.” Women who present as feminine — or gasp! on a spectrum that includes both! or none of the above! — are often considered “weak.” (Or worse.) This enlarges to treatment of books themselves. Fantasy worth taking seriously and considering not garbage is obviously dark, right? And romance, scrunch-face, well that’s just fluff (is there smoke coming out of my ears as I type this knowing people think this way? reader, there is). I believe grimdark makes the world less complicated than it is, not more. But I still see it as a valid aesthetic choice! What isn’t valid is acting is if it’s a more inherently noble or true or accomplished choice.

There’s the old saying a spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down, but that’s not apt here either — the problem is wanting to pretend the world doesn’t have any sugar in it, and that any writer who acts as if it does isn’t worthy of your time.

A world with love is a world with hope. When we see stories about love and hope and change coded as traditionally feminine and immediately dismiss them internally or in a review or wherever as corny or as not quite serious, as not worthy of appreciating for craft, we are failing. Take the work as the work. Read it and see past your preconceptions. Frankly, I can’t think of anything more serious or more challenging than using the themes I just mentioned both honestly and with light. And I would never and am not saying that stories that tackle these themes in heartbreaking, raw ways can’t be effective. What I will never understand is why we so often act like that’s the only effective way to tackle these themes. And it should certainly not be the only way in which we expect writers of color to tell stories.

And so, sure, people who do this are disrespecting the authors. But, more troublingly, they are disrespecting the audience — which is what this is all about, really. Every single thing I talk about here goes back to the fact that we’re discussing the work of women, writing for what is at least perceived as a largely female audience. No one in the world is more dismissed than teen girls (except those rare moments when we remember they change the world). What everyone is really doing when they engage in this behavior, pooh-poohing and dismissing work by women for girls and loved by girls is telling girls that the world will never take them seriously. Unless perhaps they agree to be miserable. And even then it’s a toss up…

I know I should have some rousing way to end here, but what I have to say is as short and sweet as that spoonful of sugar:

Just stop it. Read outside your comfort zones (and recommend the best of what you read! especially if! you’re! a! man! on! a! panel!). Examine your preconceptions, and don’t generalize based on them about books you know nothing about. Respect women and their work. Respect girls and what they love.*

*And don’t you ever let me hear you comparing our president to a teenage girl. Ever.