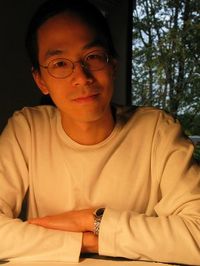

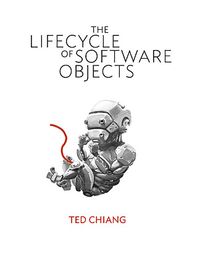

Ted Chiang is one of the world's best short story writers, as evidenced by his many, many awards (which include the Whole Set: the Campbell, the Nebula, the Sturgeon, the Sidewise, the Locus, the Hugo, and others). If you haven't been reading him, you're really and truly missing out. And while Ted's work is challenging, I also find it very accessible–if you haven't read any science fiction you liked in a long time, I bet you like his stories. (And I bet you like them if you have too.) This has been a busy year for Ted, with Small Beer Press bringing his collection Stories of Your Life and Others back into print as a tradepaper back and e-book, and a brand-new novella, The Lifecycle of Software Objects, out from Subterranean Press. (Note: The novella is available online at that link, but you should also purchase one of the gorgeous hard copies.) In addition to being one of my favorite writers, Ted happens to be among my favorite people in the entire world, and so I'm truly delighted to host this interview.

Ted Chiang is one of the world's best short story writers, as evidenced by his many, many awards (which include the Whole Set: the Campbell, the Nebula, the Sturgeon, the Sidewise, the Locus, the Hugo, and others). If you haven't been reading him, you're really and truly missing out. And while Ted's work is challenging, I also find it very accessible–if you haven't read any science fiction you liked in a long time, I bet you like his stories. (And I bet you like them if you have too.) This has been a busy year for Ted, with Small Beer Press bringing his collection Stories of Your Life and Others back into print as a tradepaper back and e-book, and a brand-new novella, The Lifecycle of Software Objects, out from Subterranean Press. (Note: The novella is available online at that link, but you should also purchase one of the gorgeous hard copies.) In addition to being one of my favorite writers, Ted happens to be among my favorite people in the entire world, and so I'm truly delighted to host this interview.

GB: As I always do, I'll start by asking you about your writing process. How do you approach your stories in terms of actual production? Was your new novella–which is, I believe, your longest work to date–different from your usual process?

Ted Chiang: My usual process is to start with the ending. The first thing I write is usually the last paragraph of the story, or a paragraph very close to the end; it may change somewhat after I've written the rest of the story, but usually not much. Everything else in the story is written with that destination in mind. I've heard many writers say that they lose interest if they know the ending too far in advance, but I have the opposite problem. I've tried writing stories when I didn't know the ending, and I've never been able to finish them.

My new novella was definitely a challenge for me, but only partially because of its length. I made a giant mistake early on, which was trying to write a 10,000 word version of the story to bring to a couple of workshops. I knew the story needed to be much longer than that, but I thought I could fit enough of it into a novelette to get some useful feedback on it. After the workshops I spent a while expanding that version, but eventually I realized that, in writing such a short version of the story, I had made certain decisions that sent me in completely the wrong direction. So I had to throw that version out completely and start over from scratch, which isn't something I had ever done before. (One result of all this is that I'm going to be much more careful about what I take to workshops.)

Work on the second version of the story proceeded more smoothly, although there were still a few hiccups. In the past I've been good at anticipating how long a story will be, but this time I was way off; I expected it would be 20,000 words, but it turned out to be 30,000. Misjudging the length so seriously made for some odd moments. I'd say to myself, "This thing is 22,000 words; how come I don't have all the scenes I need yet?" And then, "It's 25,000 words and I'm still not done? What's going on?"

GB: I understand that the entirely wonderful Subterranean Press agreed to let you oversee the design process and cover development for the novella–what was that experience like?

TC: Bill Schafer, who runs Subterranean Press, has been very good to me. A few years ago he approached me about doing a limited-edition hardcover of a story of mine, "The Merchant and the Alchemist's Gate," with two-color interior illustrations. He knew that I'd had a terrible cover-art experience with my first book publisher, so he offered me creative control over the appearance of the volume. We were both happy with the results, so he offered me the same deal for "Lifecycle of Software Objects."

Initially I didn't know if I wanted to do an illustrated edition of the novella, because I wasn't sure how well the subject matter lent itself to illustration. It's a story about artificial intelligence, and most of the action in the story consists of people sitting in front of computers, so depicting specific scenes wouldn't be interesting. Then I had an idea: as the title suggests, the novella makes a comparison between the stages in a commercial product's lifecycle and the stages of development for a living being. It occurred to me that the illustrations could show a robot undergoing the different stages of human development: a robot as a fetus, a robot as a toddler, a robot as a child doing homework, and eventually a robot having sex. That was when I thought that an illustrated edition of the novella might make sense.

I also knew I wanted an art style different from the realism that's dominant in SF art these days. I was hoping to find someone who could do something resembling sumi-e, Japanese ink and wash painting; I thought it would be cool to combine futuristic subject matter like robots with a very traditional rendering style, and I felt that style would work well with two-color printing. Unfortunately, the illustrators I contacted were either busy or uninterested in doing pictures of robots in that style. Eventually I decided to stop looking for artists who did sumi-e and start looking for artists who were comfortable painting robots.

I found Christian Pearce, whose day job is doing concept art for Weta Workshop in New Zealand; he liked painting robots, and was willing to try a loose, watercolor-ish style of rendering. First we came up with a design for the robot; then we decided on a rendering style and way of using color (black for the robotic world, red for the human world); and finally we worked on the poses for the various illustrations. The fetal robot image turned out to be the most striking one, so we went with that one for the cover.

GB: So robots in science fiction can fill lots of different roles, but a major one is to make them into helpful servants. This is, of course, right up to the moment they decide to overthrow their human masters. Do you think we have to worry about robots taking over? What about the singularity?

TC: In one respect, stories about robot uprisings are about a fear of technology, but in another respect they're about slavery. Stories in which robots are obedient are a kind of wish fulfillment for a "just the good parts" version of slavery. Stories in which robots rebel, or try to win legal rights, acknowledge that you can't have the convenience of slavery without the guilt. But these stories don't have much to do with actual robots; in the real world, robots are so far from being conscious that questions of morality don't even apply. I think it's possible that in the future, robots and software will become sophisticated enough for there to be moral implications to the way we treat them, but even then slavery won't be the appropriate comparison: it'll be more like the debate over how we treat chimpanzees. (And it's worth noting that not a lot of people get worked up over that topic.)

I don't worry about the singularity at all. I think that the singularity–meaning the idea that computers will suddenly wake up and make themselves smarter and smarter–is pretty much nonsense. Conscious software isn't going to arise spontaneously any more than word processing programs arise spontaneously. And even if we design conscious software, it won't automatically know how to make itself smarter; you and I are conscious, but neither of us has a clue about how to turn ourselves into geniuses. Even geniuses don't know how to make themselves smarter.

And now someone will say that conscious software could be run on a faster computer, which would make it smarter, and the singularity will happen that way. But the vast majority of software doesn't become better when you run it at a higher speed. Translation software doesn't produce a better translation if you run it on a faster computer; it just produces the same bad translation more quickly. The same thing would apply to uploaded people; running an uploaded stupid person at high speed wouldn't give you a smart person, it'd just give you a person who makes stupid mistakes more rapidly. If we want to make a computer as smart as a human being, there are about a million hard problems to be solved that have nothing to do with faster hardware.

GB: Your novella seems to be about parenthood as much as it is about robots. What was the motivation behind that?

TC: I believe the process of training an artificial intelligence will almost inevitably resemble the raising of a child. The reason I believe this is that traditional approaches to AI have failed so badly; it turns out you can't simply program in the information you want an AI to know. Our best hope appears to be building a learning machine and then teaching everything you want it to know. It's not strictly necessary that this training process have the emotional dimension that parenting has, but I think there'd be advantages if it did.

This need for training has major implications for how we would use artificial intelligence. As a simple example, right now it makes much more sense to hire human beings to farm gold in World of Warcraft than it does to develop an artificially-intelligent robot that can do it. Humans have a huge cost advantage over robots, because someone else has already paid for the development costs: the parents. If the only way to employ gold farmers were to give birth to a bunch of babies and raise them yourself, then developing gold-farming robots might make sense. But as long as there are human beings out there–raised by someone else–who are willing to work for subsistence wages, it'll be cheaper to hire them.

And parenting is important in ways that go far beyond matters of economics. Let me quote something Molly Gloss said about the impact that being a mother had on her as a writer. Raising a child, she notes, "puts you in touch, deeply, inescapably, daily, with some pretty heady issues: What is love and how do we get ours? Why does the world contain evil and pain and loss? How can we discover dignity and tolerance? Who is in power and why? What's the best way to resolve conflict?" We all confronted these questions as children, and the answers we received–sometimes through words but often through actions–played a big role in the kind of adults we became. If you actually want an AI to have the responsibilities that AIs in science fiction are shown having, then you'll want it to have good answers to these questions. I don't believe that's going to arise by loading the works of Kant into a computer's memory. I think it will have to come from the equivalent of good parenting.

GB: And, last, plug some other people's stuff–what have you been reading/watching/listening to that you think other people should dash out and get? How about this season of The Good Wife?

TC: I've definitely been enjoying the current season of The Good Wife. My complaint about the first season, which I mentioned when you and I last discussed it, was that too many of the law firm's clients were clearly good and deserving; that's been less so during the second season, which I think is more in keeping with the show's themes of compromise and moral ambiguity. Another TV show I've enjoyed is Terriers, which recently finished its first season; it combined the banter of a really funny buddy-cop show with the modern noir atmosphere of Polanski's Chinatown. I'm also looking forward to the next season of Justified.

Something else that I'd like to recommend is the video game Heavy Rain. For me the most notable thing about it is that it's a video game that doesn't ask you to kill five hundred bad guys in the course of the story. Not that I haven't enjoyed games that involve a lot of killing, but I'd like to see more variety in the types of games available, and Heavy Rain provides an interesting example of a game that's story driven and not focused on combat. Game critics sometimes use the phrase "ludonarrative dissonance" to describe the discrepancy between the narrative side of a game, where the protagonist behaves like a normal person, and the gameplay side of a game, where the protagonist is an unstoppable killing machine. One of the reasons this arises, I think, is that game designers want to tell a variety of stories, but only a few stories mesh perfectly with the combat mechanics that are the core of modern video games. Heavy Rain avoids this problem by using a different style of gameplay, one that works for activities other than combat, and I think it opens up a lot of opportunities for storytelling in video game form.

GB: Thanks, Ted, for stopping by and classing up the joint!

And the rest of today's WBBT stops are:

Marilyn Singer at Writing and Ruminating

Jennifer Donnelly at Shelf Elf

Sofia Quintero at A Chair, A Fireplace & A Tea Cozy

Maria Snyder at Finding Wonderland